By: Amy de Ruijter

This time on Librecast: the BBC is taking control over its data to reclaim sovereignty. For the last few years public services have hopped on the trend to outsource personalisation services to commerical parties, but the BBC is now taking the lead by creating a central open-source recommendation and data control service called My PDS. BBC’s Hannes Ricklefs and Ian Forrester talk us through the history and future of the project.

It’s the weekend, you go online, read the latest newspaper article recommended just for you, while the newest song of one of your favourite artists is playing in the background. Thinking of how to spend your evening, you check which new movies might be interesting to watch. This might feel like a moment just for yourself, but is actually created by huge amounts of data that a few services have collected about you – and people like you, according to the algorithms. BBC Research & Development thinks we can do better: it has been exploring a new data plan that puts the data of the digital services you use in one central place, called My PDS (personal data storage). From there it recommends content from these services in a user-central manner.

The problem around data collection services

The current dominance of big tech companies is a major threat to user privacy and ethical handling of data because current approaches do not reflect public service values. Organisations expend huge energy collecting and analysing data, which is primarily used to enhance products or to support targeted advertising.

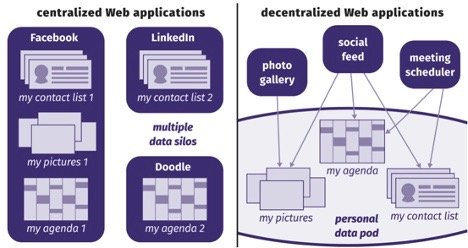

This has resulted in user data been considered as a competitive advantage and as an asset owned by the company, rather than something a user has any rights to. Therefore user data has historically been tightly coupled to its originating service and rendered non-interoperable and inaccessible. Organisations like Spotify, Netflix and the BBC operate separate technology stacks for data acquisition, analysis and use to drive recommendations and personalization of their products and services.

Ian Forrester, Senior Firestarter in Research & Development, is investigating the infrastructure of the internet from a public service point of view. He was involved in the early days of the project, that finds its origin in the Databox project in 2015 – created by Nottingham, Cambridge and Imperial Universities in the UK. ‘In 2019 a prototype device called BBC Box came out, built on Databox and powered by a Raspberry Pi, pulling your data together in one place. Databox followed the principles of HDI (Human Data Interaction): legibility, agency and negotiability. The latter is the difference between simply choosing between accepting or denying all cookies when you enter a website, and having a say in which cookies you want to accept.

A few years later, we asked ourselves: the BBC exists for the public, how do we bring this public digital sphere to them? The Databox project still exists (the code is on Github). The project split off in two different directions a few years ago. One of the projects is called The Livingroom of the Future, which explores how we can create data ethical immersive experiences within our IOT filled homes. Years later, there’s a futuristic caravan driving through the United Kingdom, bringing the living room of the future to the people. The other project is what we are talking about now: My PDS.’

Lead architect of the project, Hannes Ricklefs, says the project should be seen as a research project to understand how the BBC can advance its digital services in this time and age whilst reflecting on its public function. ‘Within BBC R&D we have been exploring new ways of storing and using data, especially personal data, for several years. Our recent project is focusing on the potential of personal data stores to the media industry, asking ourselves how search and discovery of media content can be transformed for the benefit of the public interest by using PDS and disconnecting personal data collection from services.

We saw there was a strong need for younger audiences to understand and access the different aspects of their digital lives – their mental world, financial situation, and so on – all at one glance. By combining the data held in the different services one uses, you can create a holistic picture of yourself. The project can thus be understood as a public service orientated ecosystem for personal data. Currently, when you log into a particular service, you don’t have any idea of what data is stored about you. This user centric personal storage approach changes that: it puts the user in control.’

A Solid ecosystem

Hannes: ‘For our project we have identified Solid, a set of specifications that allows for an ecosystem of interoperable applications and data, as the core technology from which to build out our technical infrastructure. Solid uses emerging W3C standards and offers open solutions to deal with decentralised identity, global identifiers, authentication and authorization mechanisms, data interoperability and query interfaces. The personal data stores created by Solid are called ‘pods’. Pods are a decentralised data store like a secure personal web server for people’s data. Once data is stored in a user’s pod, the user can decide who and what has access to it, and revoke access at any time.’

As seen in the image above, current services – centralised web applications – store personal data as part of their infrastructure. This means users must recreate this data many times, with contact lists in Facebook and LinkedIn, or a calendar in multiple applications. The fundamental difference with a PDS is that this data is created once, is represented via a common format and multiple services interact with the same data, and that the user maintains and crucially controls who has access to it and for how long.

‘We have chosen to use Solid for a few reasons. Firstly, it is open-source and is a set of proposed W3C standards – we can build our own and dig deep into any aspect for this initial trial. Secondly it is Web native – it embodies the principles of the web, especially that of universal access, which is one of the essential principles in the way we deliver our services. Thirdly, there is a large and active developer community. Finally, commercial support is available through companies like Inrupt, who want to provide an enterprise scale software solution of the Solid specification.’

The use of My PDS

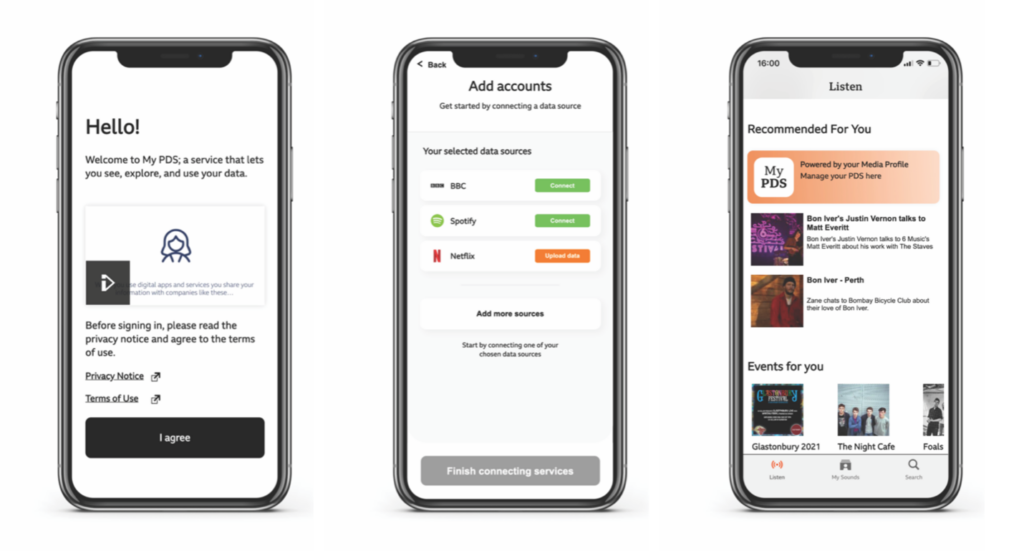

Hannes explains how the service would look like and what it would allow to demonstrate. ‘Building on our experience with Databox, and looking to explore the features and principles of a wider ecosystem including the potential role the BBC might play in shaping these new and emerging data ecosystems, we have developed an initial implementation of the overall ecosystem consisting of a web app, a trial application and more.’

The web app My PDS uses data from Spotify, Netflix and BBC accounts that has been ingested into a personal data store to create a media profile which can be exported and used by other services. The trial app, based on the BBC Sounds application, combines insights from the media profile with publicly accessible events data from other sources. In addition, supporting materials such as explainer videos, privacy policies and service FAQ’s are available. Speculative prototypes of a wider PDS proposition and compatible service propositions are being developed too.

Public versus personal recommendation

The app gives the user greater visibility of their media data, new functionality to directly edit data in their media profile stored on the PDS, and the ability to authorise its use offers greater transparency and oversight over how personal data is used to generate algorithmically determined recommendations. Hannes: ‘When your child is watching something on your various accounts, or your friends listen to their favourite music on your streaming service, it is highly likely your recommendations will be influenced by those plays. With our approach we wanted to give users more control about what gets used as input into a recommendation algorithm. The platform gives you agency over your own data from other platforms.

By creating a Media Profile, we cannot only give a better overview of your data, but also create more relevant recommendations. The BBC has all sorts of content: it spans across so many domains news, sports, live and on-demand audio, iPlayer for television programmes, education and so on. For example, when I brought in my Spotify data yesterday, I found out about clips and interviews that I doubt I would have discovered through our existing products, about the artists I listened to on Spotify earlier. One of our hypotheses is that we have more content like this and by understanding more of peoples interests we can provide more relevant content for them.’

‘Rather than building new public spaces, we want to elevate existing public spaces. Right now, it is like only being able to enter Starbucks online’

According to Ian, recommendation platforms cannot be reserved for commercial parties. ‘It doesn’t matter whether it is about a recommendation service or not, there should always be an alternative in the public discourse. As a taxpayer, I can go to a public park and enjoy the weather without having to worry about being sent away if I don’t buy an ice cream – though a café might be open for the public, you better buy some coffee. These are private spaces acting like public spaces. Rather than building new public spaces, we want to elevate existing public spaces. Right now, it is like only being able to enter Starbucks online.’

Stepping into the digital public sphere

According to Hannes, the BBC can play a more prominent role as a public service in the online sphere – by doing data ‘better’, providing more transparency of our efforts in AI and personalisation and identifying sustainable models to operate such a public online sphere. ‘It might be a long way until services adopt this new approach, however. This can hopefully provide an alternative that users will value and ask for to provide a different approach to the current commercially driven practices.

We are focusing on establishing the developer environment so we can enable other teams to join in. Additionally, we are continuing to work on establishing the overarching ecosystem. What are the governance rules, what level of data stewardship do users want and expect; but crucially, we can’t do this alone. We are keen to collaborate with partners to build out a community to help us explore this new alternative approach.’

Ian thinks we should look at the bigger picture to help the digital public sphere grow, focusing on three things: infrastructure, literacy and metrics. ‘There is a ton of new protocols and infrastructure that we need to adopt and shape. Then, we need to help people to realise a internet which has the public interest at heart. Most people understand centralised networks, maybe even peer-to-peer networks, but decentralised or distributed is just not in their digital vocabulary. As humans we like large numbers. When Facebook says they have 3,8 billion users, we say ‘oh, wow! My friends must be on there, so I will join too.’ We need a revaluation of smaller networks that make it easier to have genuine authentic connections with each other, instead of these big networks that you can disappear in. My personal hypothesis: scale could be the enemy of humanity.’

About Ian and Hannes

Ian Forrester is a well known character on the digital scene in the UK and Europe. Living in Manchester, UK, he works for the BBC’s R&D Future Experiences team. He specialises in open innovation and new disruptive opportunities; by creating value with open engagement and collaborations with start-ups, universities and early adopters. His current research is split between the future of public service in the internet age, and the future of narrative and adaptive storytelling, with a technology he calls Perceptive Media.

Hannes Ricklefs is a Lead Architect within the BBC’s Research & Development team, which drives the transformation of the BBC’s technology landscape and media capabilities. Before joining the BBC to work on frameworks, automation and human centricity, Hannes worked for over a decade in feature film VFX, building platforms that enabled the global production of Oscar winning productions such as Disney’s Jungle Book. He has a strong interest in driving projects that have a positive impact on people and society.