In our Librecast project, funded by the European Cultural Foundation, we showcase a series of Pan-European case studies about sovereign media distribution, away from big tech. We highlight these examples and try and learn from them, as we desperately need more sovereignty in our media systems to ensure a well-functioning democratic media landscape. This time: The European Cultural Backbone, which aims to build a decentralised federated network for community media providers.

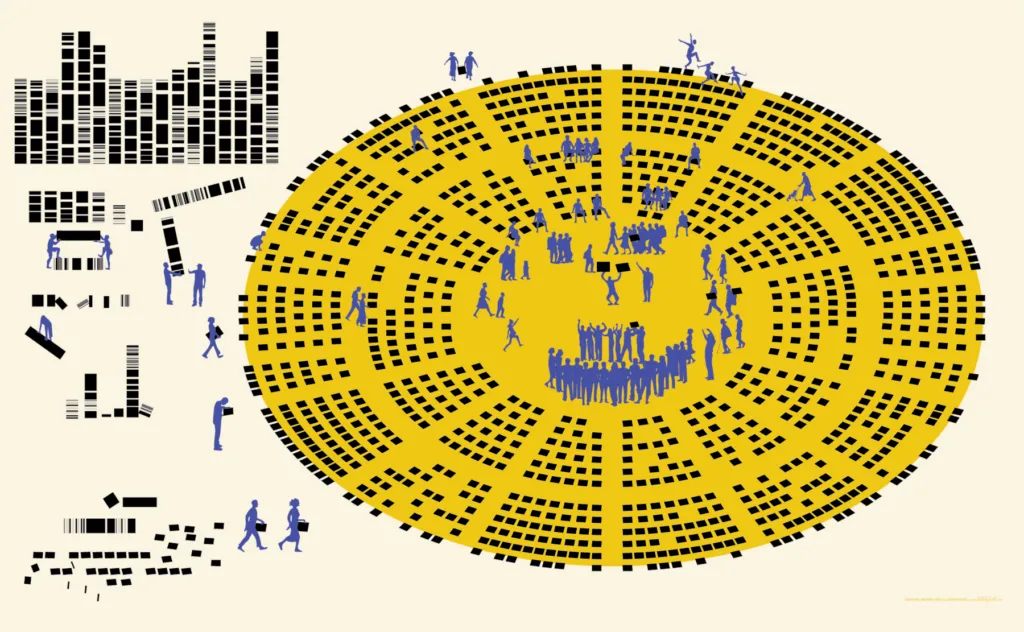

The ECB aims to build a digital infrastructure connecting different nodes made up of various European broadcasting services, providers of audiovisual content and other media outlets. The decentralised federated network will make it possible for different community media providers to exchange and share content, metadata and audiences. In order to make this vision a reality, the European Cultural Backbone 2.0 (ECB2.0) has brought together experts from all over Europe during a four-day hackathon followed up by a two-day conference, from the 23rd to the 28th of May this year (2022). In the aftermath of the conference, we talked to Ingo Leindecker and Alexander Baratsits about the ambitions of the project.

The idea of creating a continent-wide digital infrastructure is not new. The European Cultural Backbone (version 1.0) was initially pioneered in 1999. However the technology necessary for getting such a complex project up and running did not exist at the time. What was also different at the turn of this century was that the internet in and of itself was not defined by large corporations enjoying monopoly status to extent that they are doing today. While Europe has become a global leader in platform regulation, new laws can only do so much. If Europe wants to be less dependent on American or Chinese platforms, it will eventually need to develop its own, sovereign infrastructure based on European values.

REPCO: building a European Platform

Building a European digital infrastructure is not that easy. An explanation as to why a continent-wide platform has not yet been realized earlier cannot simply be found in technological hurdles that needed to be overcome. Europeans have traditionally been predominantly dependent on national and regional media outlets, most of which are partially or entirely publicly funded. Another more obvious reason for the non-existence of a shared European media space can be found in the vast variety of languages spoken within the borders of the continent.

The diversity of the European media space is something to be celebrated as much as it is something worth protecting from for-profit platforms which tend to strive for a ‘winner-takes-all’ approaches. What makes the European Cultural Backbone such a powerful concept is that is aims to take advantage of the diversity of Europe’s media spaces, without working towards homogenization or attempts to create a new platform altogether. Trusted media institutions already exist, and more importantly, all of them already have their own audience.

It therefore makes much more sense to connect the content they provide instead of creating a brand new European platform from scratch. An existing problem is that content on community media websites is usually rather difficult to find online. Search engines tend to recommend other types of media more prominently and on top of that, community media usually do not have any cross-referencing of content in place. Alexander: ‘Generally speaking, it used to be the case that people would advise against sharing content with other (media) organizations and distributors. However we think collaborating by sharing audience and thinking more holistically about media distribution could be advantageous for everyone in the long term. In the end, the audience will only benefit from media institutions realizing that others also have a lot to offer.’

The Network & Conference

For now, the team is working on a minimal viable product. Ingo: ‘We know that what we are doing is feasible, but first we need to start building. The ECB 2.0 connects different media organizations, so this would basically just mean if you search for something on one platform, it also pops up on another platform.’

In order to do so, a couple of technical hurdles need to be overcome, which have been addressed during the hackathon held between the 23rd and 26th of May in Linz. A four-day event was organised during which a group of digital experts dove deeper into technicalities of the way in which the European Cultural Backbone should take shape. Each day, a different piece of the puzzle was emphasised on ranging from data modelling, data replication and exchange protocols, to the use of various language tools, the outcome of which was summarized during a presentation on the final day of the conference.

One of the themes often mentioned was the need for a clear vision on exchange protocols. Ingo: ‘Social media protocols that are more or less in line with the values of the ECB already exist, examples of which are ActivityPub or Matrix. During the conference we extensively talked about whether we could use those. It is important to keep in mind that a long-term basis, it is not only about metadata and content, policies also play a large role. The idea behind the ECB is that each node in the network is independent and also has its independent governance. But if you replicate content, you could for instance also replicate decisions this medium made about content moderation and then decide whether to follow these decisions on your platform or not.’

Growing the network in a holistic way

The European Cultural Backbone is currently made up of a number of organisations: the Cultural Broadcasting Archive (DE), freie-radios.net (DE), AMARC Europe (European chapter of World Association of Community Radio Broadcasters) and arso (DE). Alex: ‘The aim is to invite more European organisations to be part of this network in the future. As connecting different media spaces is the goal, one can easily see that the network gets better when more organisations are. On top of that maintaining and sharing infrastructures can be done more cost-efficiently.’

The ECB could therefore potentially help to establish a paradigm shift in the way content is shared amongst European media consumers. It can bring Europeans closer together, not just by connecting them digitally, but also culturally. A lot of good quality content currently is not reaching its potential audience. For media creators as well as European (community) media organisations, there currently isn’t much of an alternative to easily share their content throughout the continent without relying on already existing platforms from outside of the European Union which have fundamentally different ideas about user’s rights as well as content ownership models. One could easily argue that a European media platform has been long overdue.

All recordings of the conference can be viewed here.

Many thanks to our talented illustrator Julia Veldman C. for creating the image above.